My Story

My name is Jessi Keavney, and I’ve chosen to be open and public about my genetic risk from the very beginning. We all have a story, and we all have something that we are particularly passionate about. To understand where I’m coming from as far as my motivations and emotional investment in Parkinson’s disease (PD) research, we have to start at the beginning.

Shown here are some pictures of my paternal grandparents along with my dad and uncle taken in the 1950s. In 2013, my grandmother passed away just one month shy of her 100th birthday from Alzheimer’s. It was at that point that I started to feel a real loss because I really wished that I had asked her more questions before her memory started to fade. I knew my grandfather had Parkinson’s and my dad did too – but she never really talked about it. And my dad was too young when his father died to remember much. He was only 7 years old and my uncle was only 11 at the time. So, here I am thinking: my grandmother and both of her siblings died from Alzheimer’s and my grandfather and my dad have Parkinson’s. Naturally, I start to wonder: what is the risk that I will get a neurodegenerative disease too? So that is where 23andMe came in. I was the first person in my family to take the at-home genetic test back in 2013, and that is when I first learned that I’m a LRRK2 G2019S carrier. It was only after I received my results that my dad was tested, and of course, it was found that he was a carrier as well.

My dad Jon, my paternal grandmother Violet, my paternal grandfather Lewis Riddick, and my uncle Lewis Norman in the 1950s

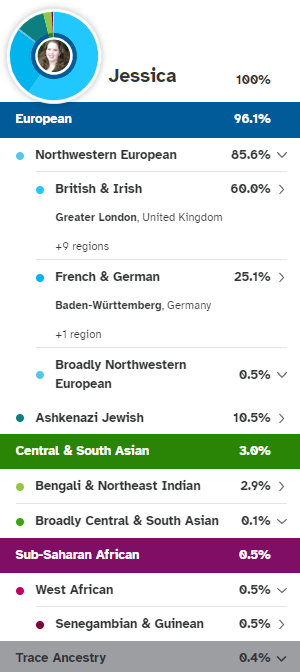

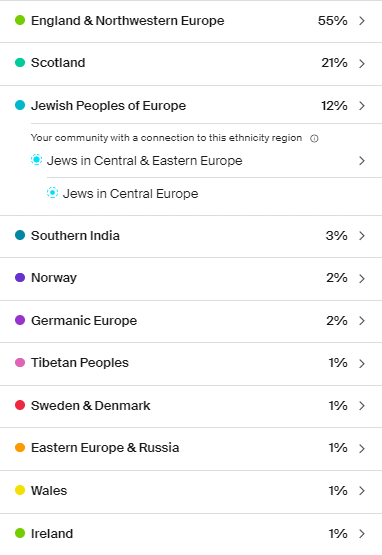

I didn’t know until after I took a DNA test and started digging into my ancestry that my great-grandmother was full Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ). Her family immigrated to Virginia from Germany in the 1800s. She is my only AJ great-grandparent so we are almost certain that she carried the LRRK2 variant that was passed down to my grandfather, my dad and me. So, my grandfather was ½ Ashkenazi Jewish, my dad a quarter, and I’m 1/8th Ashkenazi Jewish. My great-grandmother Estella lived until the age of 86 and to our knowledge had no Parkinson’s symptoms – at least none that were recognized at the time. Her death certificate lists cerebral thrombosis and gastrointestinal hemorrhage as the cause of death.

Since I was only 36 years old in 2013 and I didn’t know my ancestry in the beginning, I would not necessarily be a target in outreach programs for recruitment of carriers for research. However, literally within a week of learning about my genetic status, I was already inquiring about participating in a research study and it’s been non-stop ever since.

My 23andMe ancestry results

My Ancestry.com results

My great-grandmother Estella, paternal grandmother Violet, uncle Lewis Norman, and paternal grandfather Lewis Riddick

My paternal great-grandmother Estella

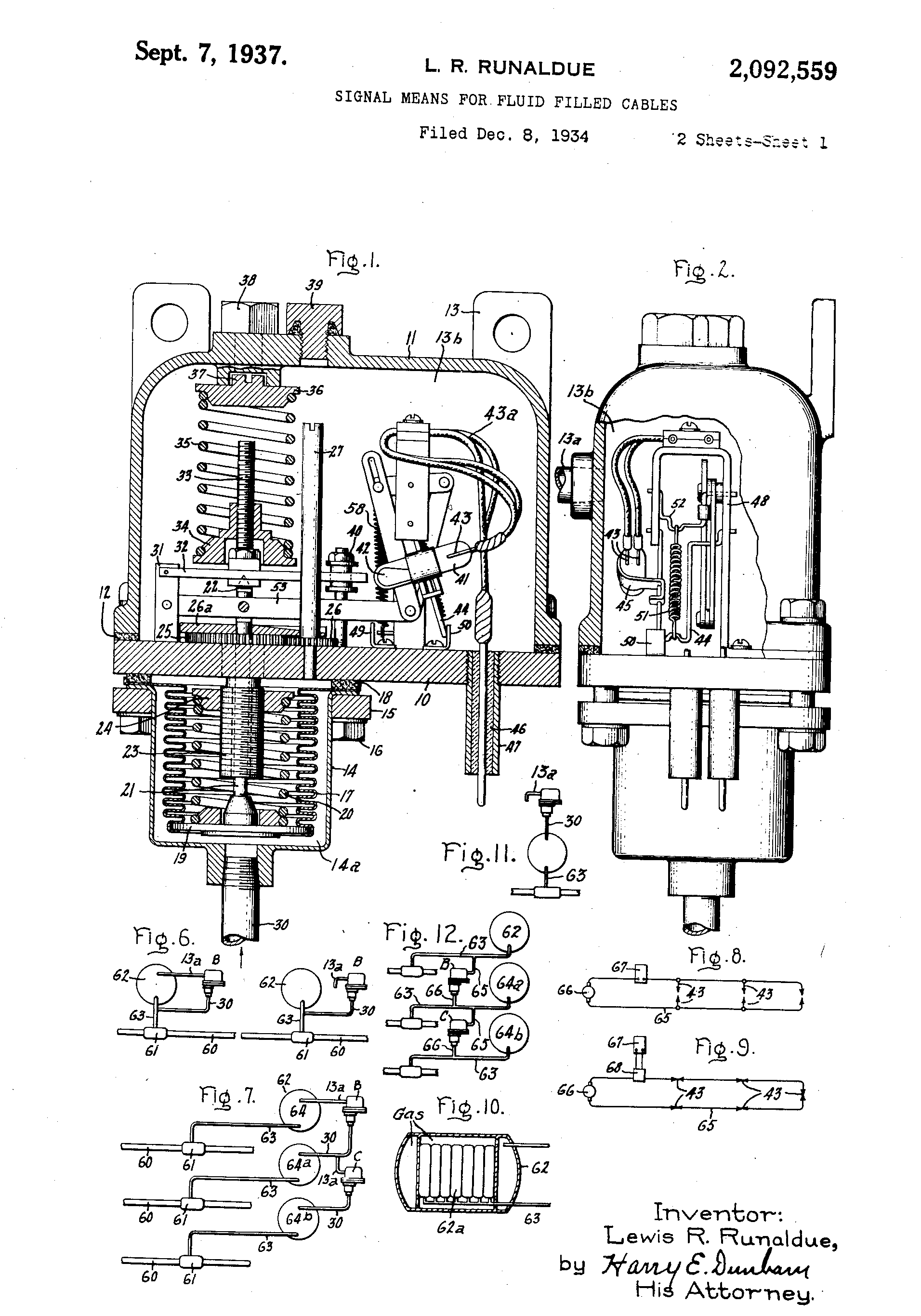

One of my biggest inspirations for research involvement is my family. My grandfather was a very intelligent man. He was an inventor and a research & development lab engineer for General Electric company. He held 16 US patents. And, during World War II, he was a member of the National Defense Research Council, and worked in a US government group that conceived and developed homing devices for torpedoes launched from submarines. My grandfather’s young family and career meant everything to him. However, at only 45 years old, my grandfather was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the early 1950s. And, to put this into perspective as shown here with my grandfather’s prescription dated 1956, this was before levodopa was even discovered. My grandfather was fairly young at only 50 years old when he made the very difficult decision to undergo two brain surgeries called pallidectomies. We have to remember that this was over 65 years ago – and neurological surgery for Parkinson’s was very experimental. For those with Parkinson’s that have had deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery or are considering DBS surgery, they know how big of a decision that is. Now imagine that you live in 1957 and the unknowns around that. I consider my grandfather somewhat of a pioneer.

Pre-levodopa prescription for Parkinson’s 1956

One of my most emotional and nostalgic experiences of research participation was when my dad and I traveled to New York to participate in a biomarker study at Columbia and we walked the same building that my grandfather was in many decades earlier. Afterwards, my dad and I spent some time at his childhood home in Massachusetts. While exploring in the attic, I found some letters addressed to my grandmother from my grandfather’s doctor after he passed away. They give you some background and insight on how it must have felt to be a young PD patient and caregiver in the 1950s.

The first letter is dated April 8th, 1957 and was written to my grandmother from J. Lawrence Pool, who was the Director of Neurological Surgery at Columbia University and the Neurological Institute of New York. He was a world-renowned neurosurgeon and one very interesting fact is that J. Lawrence Pool was actually credited as being the first person to perform deep brain stimulation on a PD patient back in 1948.

The letter from Dr. Pool regarding my grandfather reads, “Dear Mrs. Runaldue, Let me say again how deeply saddened I have been over the tragic loss of your very brave and wonderful husband. I came to know him and appreciate him so much that I was more than usually anxious to have all go well. As I wrote Dr. Budwitz, the double operation plus his high blood pressure and associated circulation hazards proved too much. To you let me extend my very deep and lasting admiration for your extraordinary devotion and exceptional courage through this long ordeal. Your bravery too will never be forgotten. Most sincerely, Lawrence Pool”

Reading this letter really hit home the enormity of what my grandparents went through. It refers to and captures their bravery and courage. My grandfather was a scientist. He knew the risks, and yet he decided to go ahead with it anyway. I think it is fair to say that he must have felt a good deal of desperation as well. The brain surgeries were his best attempt at the time to escape his suffering. For me, my grandfather’s experience serves to remind me how far we have come since the 1950s, but also how much we depend on scientific discovery and research participation to keep improving to develop safer and more effective treatments. It inspires me to do my part too.

I also found another letter that had a huge impact on me. This letter is dated April 23rd, 1957 and was written to my grandmother from Dr. Pool following my grandfather’s brain autopsy. It reads, “Dear Mrs. Runaldue, Thank you so much on behalf of us all for your extremely kind and so very thoughtful letter. This was a rare and beautiful tribute, enormously appreciated by us all. I have naturally shown your card to all the doctors and nurses concerned. The examination you so nobly permitted was a vast help to all of us concerned with this vexing problem of treating Parkinson’s Disease. For your consolation, as I wrote Dr. Budwitz, the main artery to the vital base of the brain was a mere vestige of its normal size, due to extensive thickening of its walls that had been going on for years as part of his high blood pressure disease. In a short time, this artery (the basilar) would have closed off completely and spelled the end. It was this blood vessel trouble too that caused his disease of Parkinson’s trouble and precipitated hemorrhage. The two treatments were found to be precisely in the correct and proper location, so that we know we proceeded perfectly all right with each operation. Believe me we are working hard to try to lick this horrible disease, and I am sure we will gradually continue to learn more and more. With my best regards to you and yours, J. Lawrence Pool”.

It was pretty profound to read that letter about my grandfather’s death so many decades ago. One of the things that stands out to me is that the doctor said something really bold. He said that high blood pressure caused my grandfather’s Parkinson’s. And, of course we know that Dr. Pool would have no idea about the pathogenic LRRK2 variant back then and the genetic contribution towards the etiology of his condition. And, it made me wonder: what do we think we know right now that we are perhaps misguided about? We don’t know what we don’t know. But the only way we will get there is through research. You know – why is it that a significant portion of people with the LRRK2 G2019S variant develop PD, but then again the majority of people with the variant don’t. Was Dr. Pool’s statement partially correct? Does cerebrovascular disease combined with other genetic factors cause PD in a subset of people? Well, we don’t know all of the answers yet. But, the more and more my dad and I started learning about LRRK2, the more determined we became to contribute to the growing body of knowledge about it.

Neurological Institute of New York / Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center postcard

My dad Jon D. Runaldue

Before I learned that I was a LRRK2 carrier, my dad never thought about research studies at all. But, once we knew about the genetic connection, it opened up many opportunities for both my dad and I to participate in specific biomarker and observational studies. And, for many of the studies we could support one another by doing them together. My dad and I traveled to California together to participate in studies at the Parkinson’s Institute and we both at lumbar punctures together in Washington and we participated in the early genetic registry of PPMI and we completed several studies in New York. My dad did a gait study at Emory and he also participated in the PD GENEration study and ROPAD as well. My dad really loved to talk to people and I think his favorite part of his research participation was talking to all of the researchers and coordinators at our visits.

However, the last couple of years of my dad’s life were really difficult. My dad was diagnosed around 2002 at the relatively young age of 52 and he passed away in 2021, about 19 years following his diagnosis. After my dad had several bad falls in 2019, my sister quit her job to care for my dad full-time. My mom had several major health issues of her own, so my mom was unable to care for him. I continued to work full-time, but since my parents’ house is only 3 doors down from me, I was able to help out on weeknights and on the weekends. It broke my heart to see firsthand the physical and emotional pain of my dad losing his independence. He could no longer walk, he was incontinent, and had psychosis and significant cognitive impairment. He became totally dependent on my sister and me for everything.

And, then came the COVID-19 pandemic. Something that will forever be etched in the history books on a global scale. Like so many people in this world, my family was personally impacted by the virus. Our worst nightmare happened in December 2020 when both my dad and I tested positive for COVID-19 after I took my dad to the ER for an unrelated issue. He tested negative upon admission to the hospital but both of us tested positive about a week later. I had a relatively mild case with only a headache, stuffy nose, and I completely and suddenly lost all sense of smell and taste. I had no cough, no fever, and no body aches. My dad, on the other hand, developed a very severe case with pneumonia and other complications and his bloodwork showed a full-on cytokine storm. My dad tragically passed away 2 months later on February 3, 2021.

We were absolutely heartbroken. And, I couldn’t do anything to change what happened. But one of the first things I asked myself was how do I turn something so negative into something positive? The first thing I did was started donating convalescent plasma. But when the vaccines started to become more available, the blood bank stopped testing donor blood for antibodies but instead they informed me that they really needed my platelets. After I had COVID-19, my platelet levels have been high enough that I’m able to give a triple donation in one sitting so I figured I might as well help as many cancer patients as I can. And then, I again turned to research opportunities by enrolling in 2 COVID-19 research studies. One of them looks at how genetics influences someone’s susceptibility to COVID-19 and the severity of the viral infection. The other one is a longitudinal research study (still continuing as of 2024!) that looks at the immune system’s reaction to the virus and I’m part of a sub-study that is also looking at how people with prior COVID infections react to the vaccine. With LRRK2’s association with neuroinflammation and immune system function, it does make me wonder what kind of long-term implications that my prior COVID-19 infection may have on my future neurological health and scientific research is critical to help unravel those questions.

My dad was a registered brain donor and I am too. We made that decision very early on – when we first started participating in research in 2013. Unfortunately, arrangements with the first brain bank fell through because my dad just had a lot of complicated medical issues and the first brain bank decided they couldn’t accept his gift. But we had a back-up plan with Columbia University’s New York brain bank. Words can’t fully express how grateful I am to Dr. Alcalay and brain bank coordinator Matt Surface for the last-minute arrangements. Ultimately, I think it is fitting for part of my dad to be back in the same place where his father was so I’m just so relieved that it worked out. And, Columbia has a really wonderful program where they have movement disorder fellow physicians study the clinical case for each brain donor individually and they present their hypotheses and predictions about the pathology. Then, they have the pathologist give a presentation on the actual results to see how they compare. And the family is invited to attend the case conference– which is really meaningful to us.

My best advice is to be prepared and make plans well in advance. Even if you are a registered brain donor, it still is up to the next of kin to make the final decision. So, having those discussions with your family is very important. Talk to your neurologist or movement disorders specialist and inquire about whether or not their facility has a brain bank. Also, the best and most valuable brain donations are those that have many clinical and research records during life that can then be compared to the autopsy results. Many research studies like PPMI have brain banks established for actively enrolled participants. In these cases, there is no cost to the family for donating a loved one’s brain and receiving a pathology report.

Brain donation is literally a once in a lifetime opportunity. It is extremely time sensitive and you only have at most a 24-hour window to make it happen. And it is not the same as being designated as an organ donor on your driver’s license. That is for live organ donations meant for transplants. Brain donations are different – they are for advancing scientific research. Brain tissue is very precious -one person’s brain can potentially provide information for hundreds of studies. And, donors are needed from a diverse population and from people of all ages and stages so that researchers can better understand the causes and progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

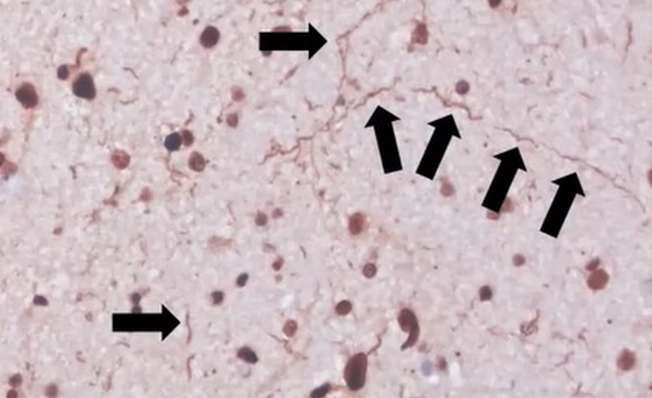

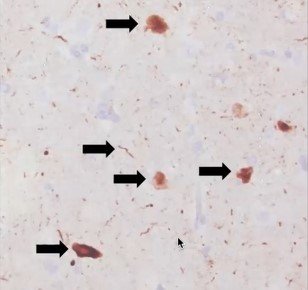

It was incredibly comforting to my family to know that even in death, my dad’s legacy lives on in research. We were able to honor his last wishes because he really wanted to help others. It also provides some closure to know the final pathology results. LRRK2-related PD in particular is very interesting from a pathological standpoint because it is highly variable – even among the same variants. Some people have pure nigral degeneration with no Lewy bodies at all. Then others have Lewy bodies but they are limited to the brainstem. Then, others like my dad have severe, diffuse Lewy bodies with additional pathologies detected. We found out that my dad’s brain resembled someone with Parkinson’s Disease Dementia, which correlates to his clinical records during life. That is interesting too, since generally LRRK2-related PD is thought to have less instances of dementia than idiopathic PD and is thought to be slower progressing than other forms. And for the first 10 years, that was true for my dad. But watching my dad significantly decline and struggle over the last several years of his life was certainly not easy.

Images from my dad’s brain autopsy are shown below. A copy of my dad’s pathology report can be found on the research results tab on this website.

I’ve had positive experiences from research participation and in many ways, it has helped me to overcome any fear. Parkinson’s doesn’t just impact the life of the person suffering with it. It truly has an impact on the entire family. As a granddaughter, daughter, wife, sister, and mother, I’m committed to doing everything I can to help both the current and the next generation. Family involvement and support definitely helps me to do that. My mom, my sister, and my husband have all participated as controls in Parkinson’s research studies. Remember that you don’t need to have a PD diagnosis to make a big impact.

One year after my dad passed away, I got a call that my uncle (my dad’s older brother) found out that he had a brain tumor after several falls. He was transferred to Mass General in Boston where he had the tumor removed. It was a rare, WHO grade II chordoid meningioma. At first everyone attributed all of his past symptoms to the tumor. I wasn’t convinced though. We’ve known for many years that my uncle had the LRRK2 G2019S variant and I would frequently encourage him to see a neurologist because I was concerned about his symptoms. But his primary care physician was adamant he just had essential tremor and there was nothing to worry about. My uncle was finally diagnosed with Parkinson’s by a neurologist at Mass General following his rehab stay after the brain surgery. And since my uncle has never been married and never had any kids and lived alone in Massachusetts, we moved him to live with us in Georgia so that we could better coordinate his care. Unfortunately, my uncle (now in his upper 70s) has progressed quickly and has dementia, a permanent catheter due to urinary retention, and is confined to a wheelchair. He requires medication to control chronic seizures. Like my dad, he has severe cerebrovascular issues that contribute to his decline.

Looking at my dad and my grandfather and comparing their age of onset (AAO) to my uncle, there is a significant difference between 45 years old, 52 years old and 76 years old. There are 24 years between age at diagnosis for the 2 brothers. And my uncle and my dad have a female 1st cousin on their paternal side that was recently diagnosed with PD and it was shown that she does not have the LRRK2 G2019S variant. So, it made me wonder about whether or not there were additional genetic variants in my family and how that may be affecting penetrance, severity, and AAO. I had whole exome sequencing done several years ago and I actually did find that I had two variants related to Wilson’s and Spastic Paraplegia type 7, which both have parkinsonian features. I looked up the SNP numbers in both my dad and my uncle’s raw data in 23andMe and I found that both my dad and I are heterozygous for all 3 of the variants listed here but my uncle only carries the LRRK2 G2019S variant. The ATP7B and SPG7 variants are relatively rare and also recessive. But, it makes me think about GBA and how heterozygous carriers may not get Gaucher’s disease but are at increased risk of Parkinson’s. Could the mechanisms for all 3 of these variants combine to cause my dad’s brain and potentially my own brain to not compensate as well and therefore accelerate degeneration? How often do we see doctors and researchers just stopping once the LRRK2 G2019S variant is uncovered? How often are other neurological conditions with overlapping symptoms considered on the gene panels?

As a mother, it is particularly motivating for me to do everything I can to try to protect my children. I have my oldest son’s permission to share that he also carries the LRRK2 G2019S variant like me and his grandfather, great uncle, and great-grandfather. And, when it was time for my annual research visit at Mt. Sinai in NY, my son came with me in 2022 to participate in his 1st study. Some people might think that at only 19 years old, he was pretty young to be participating in Parkinson’s biomarker research. But my son was born in the same year that my dad was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. He never knew his grandfather without it. He has grown up his entire life witnessing firsthand the lifecycle of the disease. He’s curious, and by contributing to research, he’s learning. Why not start lifestyle interventions early? It takes a while to develop good habits.

Like snowflakes, we are all unique individuals. None of us are exactly alike. Even among LRRK2 G2019S carriers, we all still can vary in our penetrance, age of onset, progression, phenotype, and brain pathology. That is why I’m excited about the development of improved methods for precision medicine. Studying subtypes is just the beginning. Knowledge has a way of building, and there is plenty of overlap where a discovery in one neurodegenerative disease or one genetic subtype will directly or indirectly benefit another group. But it will take great collaboration and increased research participation to get us there. My hope is that 20 years from now, I can look back and know that targeted interventions to prevent neurological diseases from ever affecting my children are a reality. I remain optimistic that we are making meaningful progress in our collective efforts towards prevention research. As Michael J. Fox is quoted, “the answer is in all of us”.