Frequently Asked Questions

If it was so difficult to watch my dad struggle, why did I want to know my genetic risk of getting Parkinson’s?

I absolutely have no regrets about learning that I’m genetically at-risk for PD. I would have actually been disappointed if I didn’t know I had the genetic variant until much later in life, because then I would have missed out on a window of opportunity to contribute to scientific knowledge early on. I hear many researchers and doctors say that they don’t recommend testing in non-manifesting people because there is nothing to prevent PD. And, to be honest, I get a little annoyed by that answer, because there IS something I can do by participating in research. The genetic variant had been there all along (since conception). Now that I know it is there, I can contribute in a really meaningful way. I already knew I had a higher risk of Parkinson’s because of my family history, but with the knowledge that I’m a LRRK2 G2019S carrier, I can help in ways that others can’t. Research participation brings me a sense of purpose – like I’m part of something much, much bigger. Ultimately, we should remember that everyone is different, and it is up to the individual to decide what they want to know. It sounds very cliché, but for many of us, knowledge itself enables a reassuring feeling of empowerment and control. It is not a foregone conclusion that I will get PD. There is lower penetrance for the LRRK2 G2019S variant so there is a source of optimism. It gives me an extra push to exercise, to eat better, to limit my exposure to toxins as much as I can, and also to keep my B12 and vitamin D levels high enough since my numbers have been historically low. And if I don’t get PD in my lifetime, it is important for researchers to understand why I didn’t since that could help with prevention strategies for others.

And, even if you already have PD, I think it is important to know if you have genetic risk variants. The current understanding of the interplay between genetics and environmental factors is continually evolving. Plus, there are many clinical trials that are starting to enroll based on certain genetic variants so it is important to know if you fall into a certain category or not.

Overall, it really feels good to do good. I love the saying “Action Cures Fear” … that rings very true for me.

In 2023, I was invited to a roundtable with academic researchers sponsored by the NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) around the topic of challenges to preclinical advancement of Parkinson’s disease therapeutics. Below are some of the questions I was asked and my responses.

From your lived experience perspective, what are the most significant gaps in PD therapeutics development, and what are some promising approaches that you have seen?

Currently, we have a lack of consensus on what defines “Parkinson’s disease” and that causes confusion – not only among clinicians and researchers, but also among patients and care partners. Personally, I prefer a broader, more inclusive definition of “Parkinson’s disease” and then have more detailed definitions of subtypes based on a combination of biology and phenotype. For example, the finding that about half of LRRK2 patients did not have a positive a-Syn SAA test sparks many questions. Some people are saying that means LRRK2-related PD and some other genetic variants should not be defined as Parkinson’s disease if there is no a-synuclein pathology. Others hypothesize that there is a different strain or level of a-syn that the test is simply not picking up in those people. I personally don’t think a-syn should be considered necessary for the definition of PD. It doesn’t make sense that those with a LRRK2 variant with parkinsonism and SAA+ would have PD but those with a LRRK2 variant and parkinsonism but SAA- would not have PD too. I absolutely believe that a precision medicine approach is the way forward for advancing therapeutics. I also believe that incorporating biology into the inclusion criteria for testing therapeutics targeted at a particular biologic trait in trials is helpful. However, we must not narrow our vision so much that we forget about the overlap and interactions amongst different pathways. Perhaps that is why I think a larger umbrella for the overall PD definition might be more appropriate.

I heard another researcher hypothesize that a-syn probably has more of a role in non-motor features like cognitive impairment. That might explain why those instances with prominent a-syn pathology like those with SNCA and GBA variants have cognitive impairment as a major feature. LRRK2-related PD has less instances of cognitive impairment – hence the variability in a-syn pathology in that subtype. If that is true, and a-syn has less of a role in motor features, testing therapeutics on a-syn targets need to have outcome measures that reflect the progression of cognitive impairment. I think that is another reason to not wholly define PD in general with a requirement of a-syn pathology since to this point, PD has been clinically defined based primarily on motor features.

Developing therapeutics is difficult because of heterogeneity. Objectives are different for people in different stages, and objectives are different for people with different biology, and objectives are different for younger patients vs. older patients, and objectives are different for people with different phenotypes. And to even further complicate it - what matters to patients might be different than what matters to care partners. Therefore, we need to gather a diverse range of perspectives of lived experience to discover what is meaningful across the spectrum. For example, in people that are at high risk for Parkinson’s, there are less immediate concerns about quality of life. We ultimately want to prevent the symptoms from occurring altogether, or to at least delay them. As someone with the LRRK2 G2019S variant, I feel that anti-inflammatory approaches are very promising. The idea that PD can be an auto-immune disease is very intriguing. For those with RBD, perhaps a-syn targets and sleep quality are important. The fear of developing cognitive impairment is a major concern. YOPD patients are concerned about being able to work longer. For my dad, his early concerns were about his tremor because he needed to be able to type and use his 10-key calculator efficiently. Later on in his disease, my dad’s #1 concern was first about urinary incontinence. Then as he advanced further, his concern was about urinary retention and he required a permanent catheter. My uncle’s #1 concern is also about urinary retention as he now has a supra-pubic catheter that is uncomfortable- albeit less so than a Foley. Urinary dysfunction has limited therapeutics and is an unmet need.

As a caregiver to my dad with more advanced symptoms, my main concern was about frequent falling, autonomic issues, and cognitive impairment. While my dad did not want to fall, he did not seem to be self-aware of his limitations and balance issues. He would do dangerous things like climb on a stool to try to reach the fan cord. My dad’s frequent falls resulted in broken bones, torn tendons, concussions, and subdural hematoma – which all contributed significantly to his decline. It was incredibly difficult to watch my dad lose his independence by not being able to walk without us next to him or watching his every move. Also, my dad had significant autonomic dysfunction that was impossible to treat. His blood pressure would skyrocket sometimes but then would get so low he would pass out – also contributing to falls. We couldn’t treat the hypertension without his BP swinging to extremes. When my dad progressed to PDD, he did not seem to be aware of his dementia. It was his caregivers that were primarily impacted. Cognitive impairment, balance / postural instability, and autonomic dysfunction are not symptoms that are relieved by dopaminergic therapies or surgery – but are incredibly important to quality of life in PD.

Concerns and symptoms evolve and change over time. Likewise, biological and phenotypic “subtypes” can change in an individual too. Flexibility is necessary to allow for that in categorization. An understanding of what might trigger changes in “subtypes” constitutes one of the major gaps in our knowledge. For the first 10 years of my dad’s PD, he was slowly progressing and was tremor dominant with no major falls and no cognitive impairment – consistent with expectations for his LRRK2 G2019S variant. He was able to continue to work and travel internationally. The last 5 years of his life was characterized by a rapid decline with freezing of gait, frequent falls, cognitive impairment, RBD, hallucinations, delusions, severe urinary and gastrointestinal dysfunction, and autonomic issues. It is very difficult to pinpoint what factors caused the dramatic change. An infection perhaps? Or other contributing factors like advancing cerebrovascular disease or hypoxia from his sleep apnea?

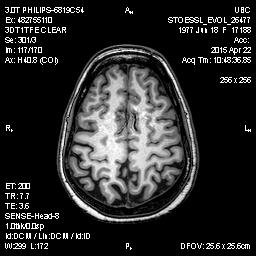

I feel that we need to start gathering observational and biological data in people at-risk for PD earlier – especially since changes are thought to occur over decades. I started participating in research relatively early at 36 years old. However, I’ve noticed that minimum age requirements for observational studies have become much higher. I’m 46 years old now – and still not at the minimum age requirement for LRRK2 participants in PPMI. For those with genetic risk factors like me with the LRRK2 G2019S variant, early participation is possible – just not really pursued. I feel like that is a missed opportunity to understand how the brain is compensating early in the development of PD. It is still valuable information to know why some people with genetic variants get PD and why some don’t. If ALL individuals that have a LRRK2 G2019S variant have increased LRRK2 kinase activity, that can’t be the only cause of PD if some people are able to overcome that.

And some things are just difficult to know in retrospect unless you are observing them in the moment. For example, my right arm noticeably does not swing when I walk and it has been that way for 7 years now. I’m sure I would never have noticed it unless I knew what to look for. My neurologist calls my asymmetric arm swing “benign” because really nothing else is evident on neurological exam and it has been that way for years. However, I have noticed a change. In the beginning, I could hold a very heavy purse in my left hand and that would prompt my right arm to swing when I walked – almost like it was compensation for my left arm being held straight because of the weight. In the last few years, it doesn’t matter if I hold something heavy in my left hand or not, my right arm will still not naturally swing when I walk. I just end up looking awkward when I walk with both arms straight by my side. And I don’t think it is because of rigidity. My arm does not have signs of stiffness. Asymmetric arm swing is a known finding in LRRK2 G2019S carriers. But it is not known how early it develops, and if it is predictive of eventual manifestation. If so, what is the underlying cause – higher LRRK2 kinase activity, or something else? By itself, asymmetric arm swing is not concerning – that is, unless it is a marker of changes that will eventually lead to PD.

There is difficulty in isolating independent variables when all of us have multiple variables that contribute to disease. I wonder why we don’t have more trials that test combination therapies? Especially in regard to prevention studies – we need to throw multiple interventions together. It is unlikely that one intervention alone will be as effective and successful as a combination strategy. Do I really care if I can say what percentage that exercise helped vs. a supplement vs. a particular diet? Do all three in combination to give it our best shot. The concept could also be applied to disease modifying trials. Researchers could design “cocktails” that are tested in certain subgroups since there is usually more than one pathway implicated.

I like the precision medicine approach that has been tested in people at risk for Alzheimer's where each individual was thoroughly evaluated and therapies were chosen based on each individual’s unique characteristics. There seems to be a greater chance of success. See https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9484109/

Do you have an example of how engaging people with lived experience of PD can accelerate therapeutics development?

While clinicians frequently interact directly with people with Parkinson’s, many lab researchers and academics remain largely disconnected and have never built relationships with people directly impacted by their research. This lack of association substantially limits researchers’ intimate understanding and appreciation for the condition. As a result, these researchers often miss out on the chance to develop strong relationships with patients that result in a deeper sense of purpose in their work. Everything becomes very abstract, and these researchers forget that people with PD are human beings and not “subjects”. Building a connection with researchers is also mutually beneficial to those with lived experience. My dad loved to talk with researchers when he participated in a study visit. It gave him hope, and he felt heard. My most positive experiences in studies are when academic researchers take the time to interact and have long conservations with me about their work. The more connections and relationships we make with researchers, the more engaged we are, and the more likely that we will continue to participate in research studies.

It is important to keep an open mind and ask questions beyond what is already established to find more clues. We need more open-ended questions on surveys to discover what is going on with participants beyond what is typically asked in questionnaires. I have (albeit infrequent) pain-free ocular migraines. The visual auras that are described in the literature are exactly what I experience. Plus, within the last couple of years I have twice experienced about 3-4 month time periods where I get daily headaches. Again, that is never asked about but I wonder how much that is associated with neuroinflammation. Likewise, no one ever asks about diarrhea but I have IBS-mixed type (just like my dad). It was extremely difficult to get doctors to understand that my dad had major QOL issues with diarrhea when only constipation is ever talked about in the context of PD. It turns out that my dad had abnormal fecal calprotectin levels, abnormal C-reactive protein levels, and even showed colitis on abdominal CT. However, his colonoscopy was negative for IBD, negative for Celiac, and he was negative for H-pylori and SIBO. Personally, I think it makes sense that LRRK2 G2019S carriers would have more IBS because of the role of gut inflammation and the notion that IBS is a disorder of gut-brain interaction. More collaboration with multidisciplinary specialists outside of neurology might help with translating therapies.

I don’t think there is enough emphasis on returning individual data/results back to participants at the conclusion of studies. I’ve participated in some biomarker studies where I did get my individual test results back but most don’t. The results don’t even need to be currently clinically actionable for researchers to return the information. It is a matter of respect and reciprocity and intellectual curiosity alone should be enough reason to disclose it. Prioritizing the return of individual results promotes trust and accountability and it recognizes the enormous contribution that participants make towards research. I also think that it would increase recruitment and retention. I was a part of large longitudinal biomarker studies (like the genetic registry for PPMI), but I’m also a participant in much smaller cross-sectional biomarker studies (breath, PET scans, gastrointestinal, skin biopsy, urine etc…) at individual academic institutions that are sometimes not connected to the larger consolidated networks. One of the few times that I received individual results back were two esophageal manometry tests I had with the Parkinson’s Institute, a facility which is now closed. The tests were abnormal – I had 90% failed peristalsis in my esophagus over repeated tests. I thought that was a very interesting finding – it makes me wonder how many other people at risk have reduced motility in their gut. It makes me sad to think those findings are lost. I’ve also been a participant in non-Parkinson’s research studies – such as those related to Alzheimer’s, COVID-19, pre-eclampsia, and fructose intolerance. You would think that an investment in certain technology and infrastructure would save money in the long-run by facilitating partnerships among various research groups. We are on the brink of precision medicine and I would have loved to have all of my data tracked and recorded over time and for me to be able to view it. Who knows what might be important to know in the future and having that individual information visible to me is valuable. Plus, I might notice an individual pattern that is not obvious to researchers when they are looking at the whole. It could spark a new avenue to pursue. We could have curated research records just like we all have individual medical records.

Keeping all of that data together would enable future n of 1 case studies that could provide clues to target intervention / precision medicine. Can we retrospectively ask permission from investigators to release and combine individual data into a secure central database for collaborative future research as long as participants consent? Wouldn’t that also save money / resources? I’ve already had whole exome and whole genome sequencing done before for research…why repeat that as long as it was from an approved source? Also, as new discoveries emerge, new tests could be performed on biobanked samples along with a rich longitudinal dataset. I know we have some of those cohorts already – but are they truly linked across all studies back to the individual? I’ve lost track of how many research studies I’ve been involved in – and I think some of my samples have been collected across cohorts.